Editor’s Bookshelf is a regular review of soon-to-be-released books that, in the spirit of Iphelia, asks important questions about how the written word and, in some cases, imagery are used to help readers reconnect with their feelings, themselves, each other, and the world around them. Iphelia’s editor, Linsey Stevens, shares her reflections—chiming in on who will be most captivated by each book’s contents and how it invites readers to return to a heart-centered way of being.

When I was in college, I had the opportunity to take a class called Jesus in World Religions. While I’d taken a comparative religion class before, Jesus in World Religions was different. I’d been raised in the church and suddenly found myself in the class—not just a student grasping at academic texts, but a feeling, believing person who, like so many others, has from childhood spent a lot of time thinking about Jesus.

When I picked up Becoming Bodhisattvas, I experienced a similar sensation as I had many times sitting in Professor Marten’s class: a knowing that I was part of what was going on in the text rather than “just a reader.”

I was initially attracted to the book because I’m regularly inspired by the idea of seva, or selfless service—which is connected in my mind to bodhisattva—a term I probably first encountered in my run-of-the-mill comparative religion class when I was 17. I’m also interested in (and benefit from) meditation, which for good reason many of us associate at least to some degree with the Buddhist tradition. Yet, I’d never committed myself to reading a Buddhist text cover to cover.

Becoming Bodhisattvas was an invitation to become a student again, learning from an incredibly articulate and down-to-earth teacher: Pema Chödrön, an American Buddhist nun, mother, grandmother, and speaker who isn’t afraid to use an expletive here or there for emphasis, which I both respect and relish given my own affinity for certain four-letter words.

I initially thought Becoming Bodhisattvas was a novel text written by Chödrön herself, but it’s actually a commentary on The Way of the Bodhisattva, an eighth-century teaching by the Buddhist monk Shantideva. So, I literally stumbled into reading my first long-form Sanskrit verse, and thanks to Chödrön’s careful dissection and annotation of the ten-part text, I made it through—thinking and feeling a great deal along the way.

I appreciate that the book doesn’t assume the reader is Buddhist or considering “converting to Buddhism” (whatever that means). Chödrön speaks to anyone who’s willing to stick with her as she explores what becoming a bodhisattva means, and points out examples of bodhisattvas including Jesus, Mother Teresa, MLK, and Gandhi, who may be more relatable to her Western readers than Shantideva or various monks in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

That said, if you’re at all familiar with the chakras, it’s worth noting that the first four chapters of the book speak to the third eye, which is to say they will have you operating from your headspace. It was not until the fifth chapter, which begins Chödrön’s presentation of Shantideva’s verses on taming the mind (or working with anger), that I was able to drop in and really start feeling nourished by the text. Even then, Shantideva relies heavily on the shock-and-scare language of his time, which Chödrön acknowledges may not be best for Westerners considering we have our own distinct struggles with the material world and relating to our bodies that Shantideva couldn’t possibly have taken into account.

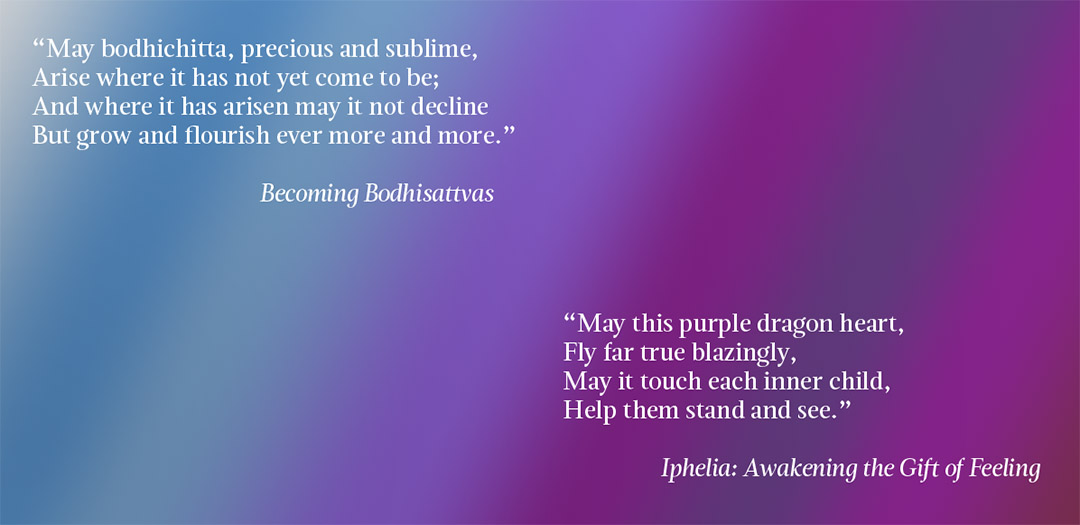

The text also oscillates in its treatment of feelings, expression, and “childishness” or the childlike parts of the self. While I am convicted that “making friends with our feelings” (language Chödrön uses but then seems to renege on), giving them healthy expression (not just trying to meditate them away), and tuning into our child selves (who are sweet, pure, and hopeful, not ignorant and selfish) is of the utmost importance, I’m still unclear on what Chödrön’s insights are in these areas.

I appreciate that Becoming Bodhisattvas, like Iphelia, acknowledges neurotic fear and bashing to bond among many other experiences and behaviors that strip us of joy and ease in our everyday lives, but know from personal experience that cultivating compassion and practicing self-sacrifice are not effective treatments in and of themselves.

Any acknowledgment of all the literature and evidence we have on trauma and abuse is completely lacking in this text, which significantly diminishes its practical value. It’s a powerful inspirational read that definitely does the work of awakening the spirit, inspiring empathy, and encouraging us to surround ourselves with supportive peers and venerable mentors, but like so many religious texts, it’s not something that’s fully-equipped to inform emotional, psychological, or physical healing.

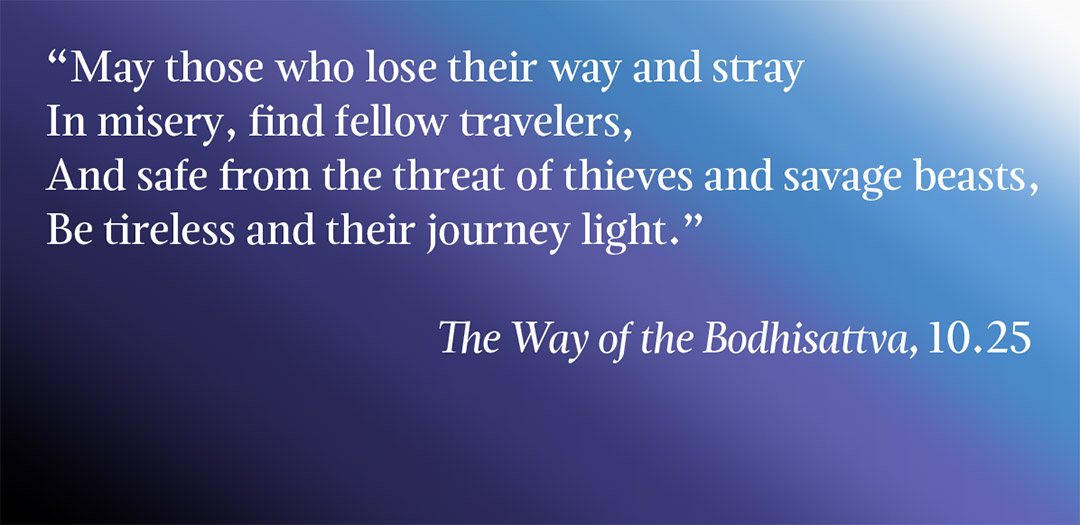

All that said, there are so many beautiful verses and striking insights in this work. Perhaps it’s best approached as something poetic and allegorical—an invitation to know a great deal more about a tradition that goes so far beyond aesthetically appealing Buddha-bust decor.

For readers interested in sampling the grace of Shantideva’s prose, start with verse 10.18 and read through to 10.26.

For those intent on reading the book in its entirety, consider beginning at the end, starting with Chödrön’s conclusion of Chapter 10, then reading through the Study Guidelines in the appendix before returning to “People Like Us Can Make a Difference,” Chödrön’s introduction to both her and Shantideva’s work.

Becoming Bodhisattvas by Pema Chödrön will be available on September 4, 2018 from Shambhala Publications. For more information on the author, visit https://pemachodronfoundation.org/about/pema-chodron/ (or, if you’re in Nova Scotia, go walk the grounds of Gampo Abbey, the Western Buddhist Monastery founded by Pema’s teacher Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche). For more on Iphelia: Awakening the Gift of Feeling, visit our book page.